In an era where the United States Supreme Court’s legitimacy is such that calling it a politically corrupted court is not far fetched. It is worth remembering that one of the most important benches in the world has had sit on it socially progressive and liberal judges who have seen justice as a force for making a better society.

William O Douglas, the longest serving justice of the Court (1939-1975), is one of those judges. Not only was Douglas responsible for the expansion of rights, such as the right to privacy in the famous case of Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) (a decision that paved the way for Roe v Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973)) but he was a committed environmentalist who, off the bench, worked assiduously to protect wilderness and other natural heritage and was also well ahead of his time in arguing for legal standing for environmental groups, rivers and trees.

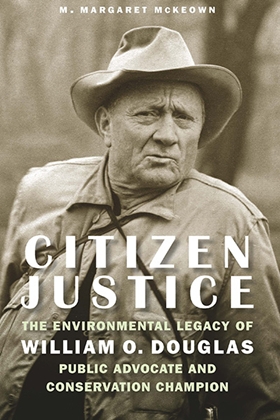

In Citizen Justice: The Environmental Legacy of William O. Douglas, published by University of Nebraska Press (2022), M Margaret McKeown, a judge of the US Court of Appeals for the Nineth Circuit chronicles, through a brilliant use of source material, Douglas’s extra-curial work and his jurisprudential thinking on environmental issues.

As she observes, however, Douglas’s lobbying of Congressmen and women, senators, Cabinet members and Presidents, including Kennedy and Johnson, would not be tolerated today (although it is nothing on the revelations about current Justice Clarence Thomas accepting trips and not declaring them). Further, she notes, even for the times, Douglas’s activities breached the judicial ethical norms.

However, there is no doubting Douglas’s critical role in saving the American landscape from the ravages of extractive industries, industrialisation and expansion of cities.

The latter was famously demonstrated when Douglas embarked on a campaign that, in 1954, included a trek of 304 kilometres to save the historical Chesapeake and Ohio (C&O) Canal which was to be obliterated by a highway in Washington DC.

Douglas’s love of the wilderness came from a childhood spent in the north west – Oregon and Washington State. Even when he went into academia at Columbia and Yale and then to Washington (he was head of the Securities and Exchange Commission from 1937 until his appointment by President Roosevelt to the Supreme Court in 1939), Douglas returned to that wilderness, every year. His summer residence was a cottage at Goose Prairie in Washington State where he would continue court work.

Douglas was a supporter of, and involved with the campaigns of the high profile, emerging NGOs of the time, the Sierra Club and The Wilderness Society.

The extent of Douglas’s lobbying for environmental causes is masterfully laid out by McKeown. The breadth of it is extraordinary. However, it is important to note that Douglas had already picked up skills in this space because he had been close to Roosevelt, part of the latter’s famous martini and card playing set.

Key allies for Douglas included senators from Washington and Oregon, including the famous Henry ‘Scoop’ Jackson, who was an earlier environmental legislation advocate in Congress. He also formed a close alliance with Stewart Udall who served as Secretary of the Interior from 1961 to 1969 under Presidents Kennedy and Johnson.

McKeown illustrates Douglas’s feat in triangulating politics, activism and judicial office in his 1960s campaign to save the Red River Gorge in Kentucky from a dam proposal. Douglas and his fourth wife Cathy Heffernan joined the protest march in 1967. At its conclusion, Douglas, having returned to his chambers at the Court, immediately, wrote to President Johnson, whom he knew, urging Johnson’s intervention to stop the proposed damming of the Gorge. It worked. The project’s momentum slowed down and it was abandoned in the early 1990s.

On the bench, Douglas was the first to recognise that trees and other inanimate objects like rivers could have standing. Douglas had been influenced by a seminal article by Christopher Stone, “Should Trees Have Standing? – Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects”, published in the Southern California Law Review in 1972 (1).

Douglas had the chance to apply Stone’s thesis in a 1972 landmark environmental case concerning standing, Sierra Club v Morton (2). In his dissent, Douglas reasoned:

“Inanimate objects are sometimes parties in litigation. A ship has a legal personality, a fiction found useful for maritime purposes. The corporation sole – a creature of ecclesiastical law – is an acceptable adversary, and large fortunes ride on its cases. The ordinary corporation is a ‘person’ for purposes of the adjudicatory processes, whether it represents proprietary, spiritual, aesthetic, or charitable causes.”

Therefore, Douglas wrote:

“… it should be as respects valleys, alpine meadows, rivers, lakes, estuaries, beaches, ridges, groves of trees, swampland, or even air that feels the destructive pressures of modern technology and modern life.”

Douglas died in 1980. He was and is, still, much admired by progressives and those who believe that the law must be applied in the context of the times in which it operates. Former High Court Justice, Lionel Murphy, was an admirer of Douglas for that reason.

This is a fascinating book about a ‘big man’. Unorthodox, iconoclastic and flawed, Douglas however is an environmental movement icon because he used his elevated position in society to enhance the earth (3).

Greg Barns SC

Chambers

18 August 2024

Footnotes:

(1) Christopher D Stone, “Should Trees Have Standing? – Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects.” (1972) 45 Southern California Law Review 450.

(2) Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 (1972).

(3) Ibid 742-743.